Al igual que su tema, este libro oscila. Las ideas emergen, se alejan en la distancia y vuelven a aparecer. Jóvenes inocentes que parecen disfrutar balanceándose en un primer plano bucólico, en pinturas, son desenmascaradas para el espectador por pastores que miran lascivamente desde atrás. El capítulo sobre «emociones» no abarca nada de lo que los estudiantes de psicología podrían esperar, ninguna de esas «seis emociones básicas» que enseñan los libros de texto de psicología de sus cursos. Cuando Moscoso habla de emociones, se refiere a la conciencia del «movimiento», tomando prestada la antigua idea romana de motus animi (los movimientos del alma), para describir las pasiones humanas. Cicerón las llamaba «perturbaciones» y, siguiendo su ejemplo, las emociones de Moscoso incluyen vértigo, angustia y suspensión. Seguramente desea desorientar (otra e-moción) a sus lectores, mientras nos convence de que el propio pensamiento está en constante flujo, que nuestros cuerpos se balancean, que tenemos la capacidad (de hecho, la tendencia) de amar y odiar a la misma persona al mismo tiempo. Balancearse es una alegría para los niños; algo profundamente incómodo y desconcertante para muchos adultos. Perturba la jerarquía y las categorías. Es completamente flexible en su significado, y abarca desde el movimiento de un pobre diablo colgado de una soga hasta el ritmo del acto sexual.

Moscoso escribe en prosa, pero su libro también se puede leer como poesía, ya que está lleno de alusiones, conexiones y giros de frases que bien podrían ser analizados y debatidos en un curso de literatura. Al igual que Auden y Eliot, Moscoso es formidablemente culto y ferozmente erudito. Este libro no pretende ser tanto una historia que debemos absorber, como un desafío en el que participar. En primer lugar, debemos abrazar nuestra Wanderlust y acompañar al autor mientras viaja desde la antigua Grecia hasta el sudeste asiático, luego a China, Europa y Asia. Y, dado que los saltos geográficos y cronológicos son insuficientes para abarcar todo el alcance de su tema, nos lleva, casi sin aliento, a la sala de examen del médico. Al final, nos encontramos en el mundo de la pornografía, donde se pueden explorar las infinitas variaciones del sexo y su maquinaria oscilante sin vergüenza ni miedo.

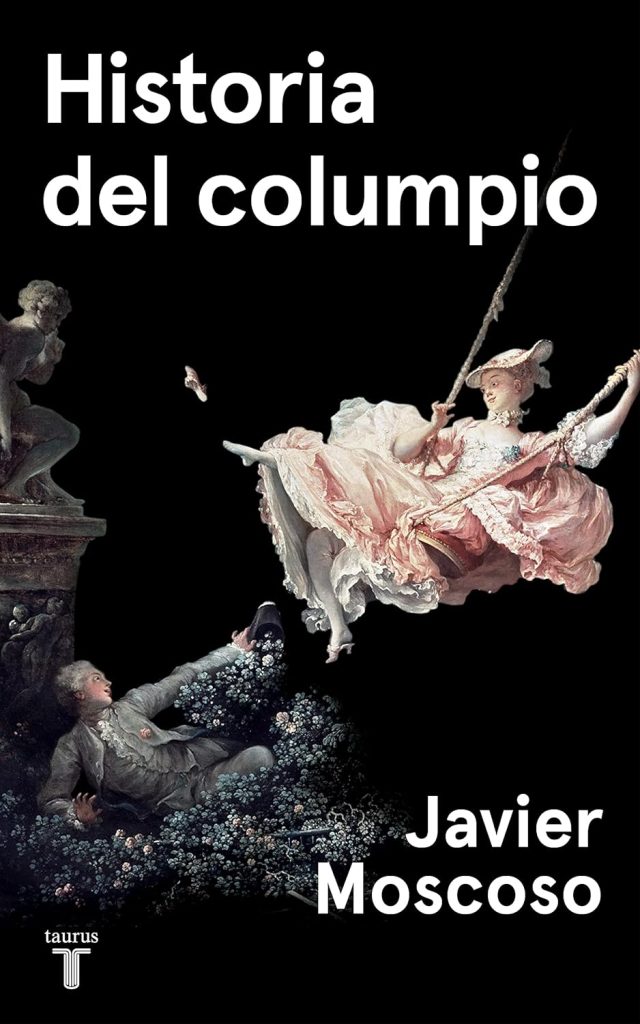

Para Moscoso, todas las similitudes entre lugares y tiempos no sugieren universalidades predefinidas, sino más bien una mezcla de naturaleza y cultura, «partly learned and partly innate» (p. 62), [«en parte innato y en parte adquirido» (p. 37)]. Por eso su historia no es como las historias ordinarias: con un principio, un medio y un fin. No hay forma de determinar el comienzo del balanceo ni rastrear su desarrollo, porque ese gesto, aun cuando tiene raíces en la biología, se comprende y se utiliza de manera diferente en diversos contextos culturales y en diferentes períodos históricos. Cuando un niño de hoy se balancea alto, grita: «¡Mamá, mírame!», No es exactamente el mismo grito de curiosidad que el de la joven de la pintura El columpio de Fragonard dirige a su apuesto galán, pero hay más afinidades entre ellos de las que imaginamos.

A lo largo de todo el libro, Moscoso hace del cuerpo la clave de su discusión. Mientras que Descartes afirmaba que primero pensaba, luego existía, Moscoso insiste en que para que un pensamiento signifique algo debe estar arraigado en nuestros sentidos, «Those who must know must first believe, no doubt. But even before that, they must feel» (p. 69) [«El que debe conocer debe primero creer, sin duda. Pero antes de creer deberá sentir» (p. 82)]. Las doctrinas religiosas pueden predicarse, pero deben experimentarse antes de poder ser autorizadas como reales por los creyentes. Cantamos los salmos en un canto rítmico, probamos la Eucaristía, tocamos la Torá. En la antigua Grecia, el balanceo era parte de una festividad religiosa primaveral: cualquiera que sea su función exacta, imitaba tanto el sexo como la muerte en su movimiento dentro y fuera del reino terrenal.

Los rituales religiosos son de gran importancia cultural para Moscoso. Argumenta que canalizan impulsos universales (universales porque están arraigados en el cuerpo) de forma que los controlan y les dan un significado coherente. Por ejemplo, en la fastuosa ceremonia Triyamphwai, los gobernantes tailandeses (siameses) movilizaban un columpio gigante en el que hombres que se hacían pasar por dioses realizaban tareas aparentemente imposibles. Aquí, el sistema vestibular del cuerpo, un universal, era empleado de manera especialmente dramática para dar brillo religioso al Estado.

Pero, uno podría preguntar, ¿es realmente universal el cuerpo? Cuando decimos que el balanceo es en parte innato, ¿es esa «innatez» la misma para todos? Un niño criado en una ciudad contaminada por el humo tiene un cuerpo diferente al de un niño criado en el campo. En el nivel más básico, su ADN habrá estado expuesto a diferentes metales, contaminantes del aire, y así sucesivamente. Estos factores trabajan para mutar y degradar nuestros genomas. ¿Es equivalente el cuerpo de un niño que ha sido fuertemente envuelto desde el nacimiento al de otro al que se le permite moverse libremente? Uno podría imaginar que una niña que apenas puede caminar porque sus pies han sido atrofiados por la ligadura desde la infancia tiene experiencias vestibulares diferentes al joven atleta que entrena para los Juegos Olímpicos. Los genes humanos se ven afectados tanto por el entorno interno en el que las células se bañan como por el mundo externo (natural y creado) en el que la piel absorbe, la boca ingiere y los oídos oyen.

Moscoso no habla de ADN, pero ciertamente ve formas en las que diferentes cuerpos sentirán de manera diferente en entornos particulares. En la Edad Media, cuando los pies de la mayoría de las personas rara vez se levantaban del suelo, «we cannot even be sure that the swing’s effects were not felt with fear»(p. 156), [«en relación al columpio, no podemos siquiera asegurar que sus efectos no se sintieran con miedo» (p. 168)]. En resumen, lo «innato» para los campesinos medievales era muy diferente de lo «innato» en la época de Fragonard. Del mismo modo, nuestra era gusta del rock and roll, imitando el trajín animado de la vida moderna. Dependiendo del sistema social y político, las mujeres y los hombres pueden necesitar balancearse por razones muy diferentes. Las mujeres en sociedades represivas tienden a encontrar liberación en días especiales en los que tienen la oportunidad de balancearse, invirtiendo o eliminando así jerarquías sociales. Para ellas, el balanceo funciona como una especie de metonimia de la oscilación social, permitiendo que ocurra una perturbación que a pesar de todo no cambia realmente el viejo orden. Los hombres en tales sociedades también pueden disfrutar del balanceo, pero más probablemente por la oportunidad de soñar «of collecting and possession» (p. 146).

Un libro como este, que yuxtapone la filosofía de Nietzsche con una discusión de sobre las características del juego, la Virgen María con la historia del falo, no es fácil de leer, aunque siempre es divertido. Pero ya sea leído por placer o con meditación profunda, vale la pena el esfuerzo. Arc of Feelings es una contribución brillante e importante a un campo en crecimiento que entrelaza la historia, el cuerpo, las emociones y la experiencia. A eso, añade la religión y la sociedad. Abordar el tema del balanceo requería mucho valor. Los columpios de hoy se consideran «demasiado infantiles». Moscoso le da a este tema hasta ahora pasado por alto e incluso denigrado una importancia inesperada. El patio de recreo de los niños, con sus balancines, giradores, trampolines, juegos y toboganes en espiral, se convierte en una metáfora de los dolores y placeres sensoriales, las subidas y bajadas de la vida terrenal en sí misma. El juego de los niños nunca ha estado tan lleno de significado.

Barbara Rosenwein, reconocida medievalista, es profesora emérita de la Universidad de Loyola, Chicago. A ella se debe el uso académico de la expresión «comunidades emocionales».

Regarding the Swing

Like its subject, this book swings. Ideas come to the fore, recede into the distance, reappear again. Innocent-seeming young girls happily swinging in a bucolic foreground in paintings are unmasked for the viewer by leering shepherds in the back. The chapter on “emotions” covers nothing that psychology students might expect, none of those “six basic emotions” that their psychology course textbooks teach. When Moscoso talks about emotions, he means the feelings of “motions,” borrowing from the ancient Roman idea of motus animi (the motions of the soul) to describe the human passions. Cicero called them perturbations, and following his lead, Moscoso’s emotions include vertigo, anguish, and suspension. He surely wishes to disorient (another e-motion) his readers, as he convinces us to see that thought itself is in constant flux, that our bodies sway, that we have the ability (indeed, the tendency) to love and hate the same person at the same time. To swing is a joy for children, profoundly uncomfortable and bewildering to many adults. It upsets hierarchy and fixed categories. It is utterly flexible in meaning, describing the movement of a poor devil dangling from a noose as well as the rhythm of sexual intercourse.

Moscoso writes prose, but his book is also good to read as poetry, as it is filled with allusions, connections, turns of phrase that might well be analyzed and debated in a literature course. Like Auden and Eliot, Moscoso is formidably well-read and fiercely learned. In this book he is not so much tracing a history that we are to absorb as he is challenging us to participate in its action. First and foremost, we must embrace our Wanderlust and tag along with the author as he travels from classical Greece to Southeast Asia, thence to China, Europe and Asia. And, since geographical and chronological leaps are insufficient to cover the entire scope of his topic, he takes us, nearly breathless, into the physician’s examining room. At the very end we find ourselves in the world of pornography, where the infinite variations of sex and its oscillating, catapultic machinery can be explored without shame or fear.

For Moscoso, all the commonalities among places and times do not quite suggest pre-determined universalities but rather a mix of nature and culture, “partly learned and partly innate.” (p.62) This is why his history is not like ordinary histories, with a beginning, middle, and end. There is no way to determine the beginning of the swing nor to trace its development because it is rooted in biology and yet is understood and used differently in various cultural contexts and at different historical periods within those cultures. When today’s child swings up high, she calls out, “Mommy, look at me!” It is not quite the same cry for a peek that the young swinging beauty asks of her handsome swain in Fragonard’s painting “The Swing”, but there are more affinities between them than we imagine.

Throughout, Moscoso makes the body key to his discussion. While Descartes declared that he first thought, then existed, Moscoso insists that for a thought to mean anything it must be rooted in our senses “Those who must know must first believe, no doubt. But even before that, they must feel.” (69) Religious doctrines may be preached, but they must be experienced before they can be authorized as real by believers. We sing the psalms in rhythmic chant, we taste the Eucharist, we touch the Torah. In ancient Greece swinging was part of a spring religious festival: whatever its exact function, it mimicked both sex and death in its movement in and out of the earthly realm.

Religious rites are of key cultural importance to Moscoso. He argues that they channel universal impulses (universal because rooted in the body) in ways that harness, control, and give them a coherent meaning. For example, a lavish Triyamphwai ceremony used to be celebrated by Thai (Siamese) rulers with a gigantic swing on which men impersonating gods performed seemingly impossible tasks. Here the body’s vestibular system, a universal, was nevertheless employed in a particularly dramatic way to add give religious luster to the state.

But, one might ask, is the body indeed universal? When we say that the swing is partly innate, is that “innateness” the same in all? A child raised within a smog-filled city has a different body than one brought up in the countryside. At the most basic level, their DNA will have been subjected to different metals, air pollutants, and so on. These work to mutate and degrade our genomes. Is the body of a boy tightly swaddled at birth equivalent to another allowed to move freely? One imagines that a girl who can hardly walk because her feet have been stunted by binding since infancy has different vestibular experiences than the young athlete who trains for the Olympics. Human genes are affected both by the internal environment in which cells bathe and the external world (natural and created) in which the skin absorbs, the mouth ingests, the ears hear.

Moscoso does not talk about DNA, but he certainly sees ways in which different bodies will feel differently in particular environments. In the Middle Ages, when most people’s feet rarely left the ground, “we cannot even be sure that the swing’s effects were not felt with fear.” (156) In short, the “innate” for medieval peasants was very different from the “innate” in Fragonard’s day. Similarly, our age likes to “rock and roll”—mimicking the jazzy jive of modern life. Depending on the social and political system, women and men might need to swing for very different reasons. Women in repressive societies tend to find release in special days in which they have the chance to swing, in that way reversing or eliminating social hierarchies. For them, the swing functions as a kind of metonym of social oscillation, permitting unsettling to happen without really changing the old order. Men in such societies might like to swing as well, but more likely for the chance to dream “of collecting and possession.” (146)

A book such as this, which juxtaposes the philosophy of Nietzsche with a discussion of card games, the Virgin Mary with the history of Phallus, is not easy to read, although it is always fun. But whether read for pleasure or hard meditation, it is worth the effort. For Arc of Feeling is a brilliant and important contribution to a growing field that imbricates history, the body, emotions, and experience. To that, it adds religion and society. Taking up the swing needed a good deal of courage. Swings today are “outgrown.” Moscoso gives this hitherto overlooked and even demeaned topic unexpected significance. The children’s playground–with its “jungle gyms,” teeter-totters, spinners, trampolines, jungle gyms, and spiraling slides—becomes a metaphor for the sensory pains and pleasures, the ups and downs of earthly life itself. Child’s play has never been so full of meaning.